Minnesota’s Tom Fisher: Making the World Better by Design

Sunday, July 31, 2016 at 7:48PM |

Sunday, July 31, 2016 at 7:48PM |  Susan Schaefer |

Susan Schaefer | Interview and Photos by Susan Schaefer

Tom Fisher, Director, University of Minnesota’s Metropolitan Design Center

Tom Fisher, Director, University of Minnesota’s Metropolitan Design Center

What is essential is invisible to the eye, says the fox.

- Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

We tend to think of design in terms of the visible world around us: the buildings we occupy and the products we use. But the ‘invisible’ systems that we depend on in our daily lives – the infrastructure buried beneath our feet or in our walls, the educational and health systems that we all experience as we age or become ill, and the economic and political systems that affect us in myriad ways over time – remain just as much designed as anything that we inhabit or use.

- Thomas Fisher, Designing Our Way to a Better World, University of Minnesota Press

Fisher inscribes his latest book, Designing Our Way to a Better World

Fisher inscribes his latest book, Designing Our Way to a Better World

As we sit is his subterranean yet sun-filled offices in the iconic Rapson Hall on the University’s East Bank, Fisher glows like a schoolboy as he discusses his life, work, new book and recent projects. If anyone is capable of linking the design process to life’s processes, Fisher is uniquely qualified and Minnesota is lucky to have him. As the saying goes, “He could have chosen anywhere.”

As a young university architecture student in Cornell University, Cleveland-born Fisher had a remarkable summer encounter: In one of those ‘life changing’ moments he came face-to-face with the intellectual giant, Lewis Mumford, architectural critic for The New Yorker, noted for his study of cities and urban architecture amongst other scholarly pursuits.

Young Fisher, in awe of his intellectual prowess, boldly asked: “How do I get to be like you?”

That query was met with Mr. Mumford’s serious and sagacious advice, “Go study how the mind works.” Thus began Fisher’s trajectory from architectural education to what can best be called “the study of big ideas” in an exceptional graduate program offered through Case Western Reserve.

Earning a Master’s Degree in Intellectual History can be an intriguing cocktail party conversation starter, or not. But Fisher’s passion for ideas and ideals is alarmingly pure, rendering him approachable on lofty, mind bending topics. And, his enthusiasm is disarming – tangy and cool as vodka and ginger over ice on a hot day. Lewis Mumford would be proud. Fisher wants to know, and doggedly pursues, “How we should live.”

…

I first met Fisher in 1995, shortly after he’d come on board as Dean of the University’s College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. As the Director of Communications for local architects, Cuningham Group, I was tasked to help introduce to our region the newly appointed head of urban planning, the late, great Victor Caliandro, highlighting his illustrious expertise as a riverfront designer.

In response, I created a public affairs program, The Minneapolis Riverfront: Vision and Implementation, to draw attention to him and the then-abandoned central Minneapolis Riverfront.

Rather than taking the customary marketing communications tactic, I suggested an innovative public affairs approach to establishing the firm as a leader. We convened multiple key players who had been long engaged about how best to develop the then dormant riverfront, our now vital riparian treasure.

Tom Fisher was first on my list of local stakeholders. He joined our effort and lent his considerable brainpower to the project that included local, national and international architects, to reimagine the riverfront. We have remained friends and colleagues ever since.

…

Not many ordinary Minnesotans understand the heft and impact of the University’s Metropolitan Design Center, soon to be renamed the Minnesota Design Center. Nor is the story of how the School of Architecture morphed into the College of Design much known outside the field. Yet, Fisher’s and the University’s leadership add essential gravitas to Minnesota’s role in this critical and cutting-edge field.

Q: Please talk about the evolution of the University’s College of Design, why you stayed on to shepherd the transition, and what it means to our region.

A: When the College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, where I was the dean, merged with the Department of Design, Housing, and Apparel to become the College of Design in 2006, I stayed on as the dean because it represented where I thought the design community needed to go.

By having all of the design disciplines in one college, we have been able to develop new interdisciplinary programs, like product design or human factors. This new college has also positioned us well to participate in the growing interest in design thinking, which is the topic of my recent book. The redesign of the systems that are not working well – our educational system, our political system, our economy, our infrastructure, etc. – may be one of the most important tasks before us and it is something to which our Center and our College has to contribute.

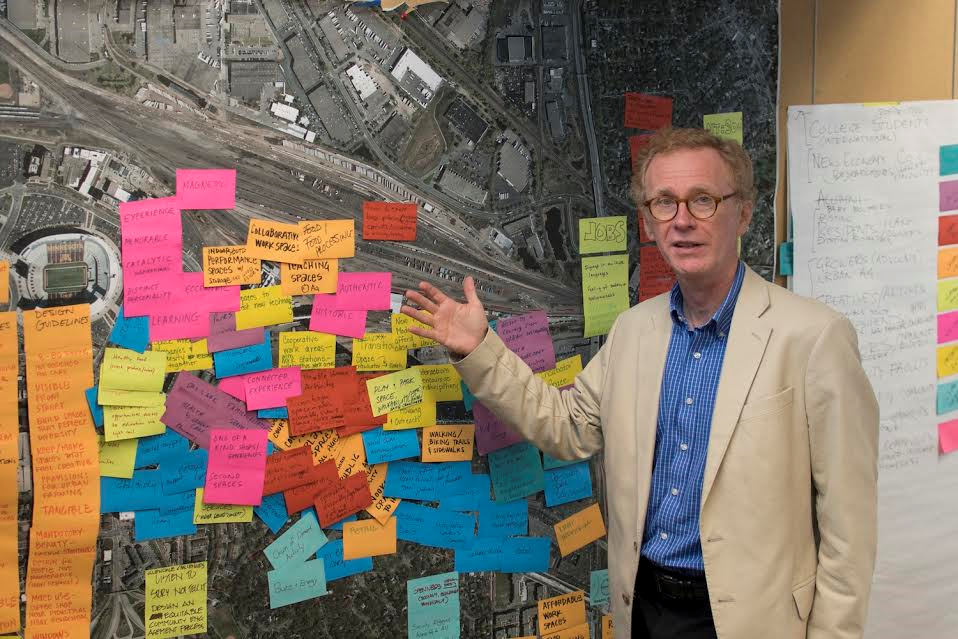

Fisher demonstrates visualizing design

Fisher demonstrates visualizing design

Q: Back when I convened the Minneapolis Riverfront: Vision and Implementation program, William Morrish was the Director of the Design Center for American Urban Landscape. Was that a precursor of the Metropolitan Design Center? How and when did the Metropolitan Design Center begin?

A: Yes, the Metropolitan Design Center, which is in the process of changing its name to the Minnesota Design Center to reflect its statewide mission, is the same entity that Bill Morrish and Catherine Brown led over 20 years ago as its first directors. We changed the name because the Design Center for American Urban Landscape seemed too long and too hard for many people to remember. I am the fourth director of the center.

Q: Who supports the Center and what benefit does it bring to our region?

A: The center is supported by a generous endowment by the Dayton Hudson (now Target) Foundation and we have had on-going support from the McKnight Foundation.

In terms of the Center’s importance, we are living in a period of unprecedented urbanization, with record numbers of people moving into cities, and a period in which we face profound economic, environmental, technological, and social changes. The Center provides a platform and a place where a diverse group of people can work on projects related to these issues, helping communities and organizations recognize and respond constructively to the opportunities that we face in Minnesota as well as nationally.

Q: My work as a public relations and public affairs professional puts me in almost daily contact with members of the ‘design community,’ from graphics to architecture to urban to product design and more. My respect for designers is immense and sincere, yet I perceive that their (modern) training and education, and view held by society, often locks these elegant problem solvers into insular boxes. They have been essentially handicapped or ‘siloed’ by internal and external points of view. Your latest book and your very ethos seem to push back hard on this insularity, advocating for ‘design thinking’ by designers as a 21st century opportunity to break out of these boxes. Please elaborate and explain specifically how the work you’re doing and education you’re providing at the Metropolitan Design Center can/will change this equation, allowing those bright designers a more impactful role in society.

A: The design community is undergoing a transition from strictly defining itself in terms of outcomes – architects produce buildings, industrial designers products, etc. – to more broadly defining itself in terms of the knowledge, processes and methods used to do such work, which has applications far beyond its traditional outcomes.

We do this in our work at the Center. For example, we are working with Allina Health to teach design thinking skills to the leadership of the CDC (Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, GA) so that that organization can respond more creatively and flexibly to global health challenges. We are also working with four countries (Hennepin, Ramsey, Anoka, and Dakota) to reimagine the adult foster care housing system to give residents greater choice.

In all of these cases, we co-create with the groups we work with and build their capacity to do this work without us. I would love to see design thinking skills taught as part of every student’s education, since we all have the capacity to be more creative than we are often allowed to be.

Q: What are the pros and cons about working in a university environment?

A: The pros of working here are the great students we have to work with and the faculty and practitioners who bring a lot of knowledge and passion to the work they do. The cons are mainly on the HR side: our work requires a degree of flexibility and speed of work that doesn’t fit well with the HR policies and procedures of universities, geared to the hiring of long-term faculty and staff.

Q: Important to our readership is the Central Mississippi Riverfront. What do you see as working, what missing in the current overall Central Mississippi Riverfront development?

A: The planning for the central Mississippi has done a lot of good work, with some of the nation’s top landscape-architecture talent working on it, creating a public realm that will be accessible to and enjoyed by everyone. What’s missing is a mechanism to enable a diverse population to live near and next to these open spaces. While we know that affordable housing can greatly reduce other social costs, we lack the means to provide it and so we have extraordinary open spaces along the river that the less affluent have to travel far to see.

Q: What else should our readers to know about yourself or your work?

A: I have always wanted my work to speak for itself and not have it be about me. I am married, have two grown daughters, both of whom are married and living in the area, and have a grandson and a grand daughter on the way. And I follow the advice of the Stoics: focusing on what I can control and where I can make a contribution, without spending any time on what I can’t control or can’t contribute.

Fisher with a co-creator at Towerside: MSP Innovation District’s ribbon cutting

Fisher with a co-creator at Towerside: MSP Innovation District’s ribbon cutting

Speaking of making a contribution, as we conclude our interview, Fisher enjoins me to hop the light rail to attend the ribbon cutting of another precedent-setting project on which he’s been involved, Towerside. Called an MSP Innovation District, Towerside is 370 acres extending from the University’s campus in Minneapolis east into St. Paul, the only duly designated innovation district in the Twin Cities with the intent to mix entrepreneurs, residents, researchers, developers and businesses with a new, restorative, healthy and arts-inspired community. Truly, design thinking made visible.

Susan Schaefer can be reached at susan@millcitymedia.org.