Saint Anthony Falls

In 1680, the falls became known to the Western world when they were observed and published in a journal by Father Louis Hennepin, a Catholic friar of Belgian birth, who also first published about Niagara Falls to the world's attention. Hennepin named them the Chutes de Saint-Antoine or the Falls of Saint Anthony after his patron saint, Anthony of Padua.

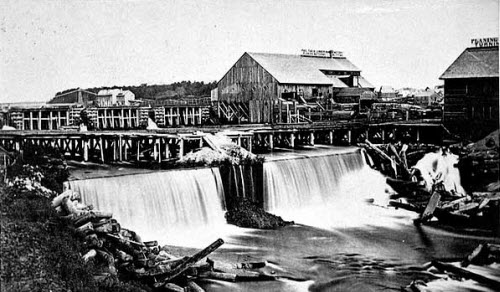

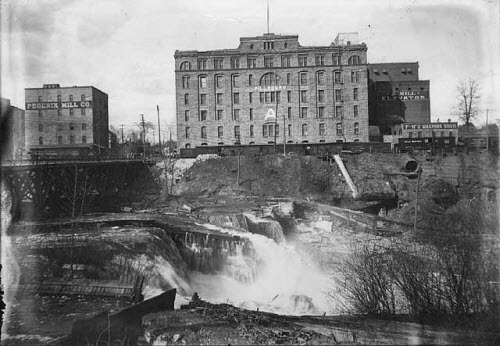

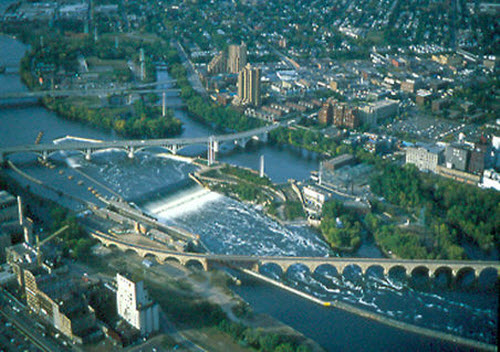

Saint Anthony Falls, located in the Historic Mill District of Minneapolis, Minnesota, was the only natural major waterfall on the Upper Mississippi River. The natural falls was replaced by a concrete overflow spillway (also called an "apron") after it partially collapsed in 1869. Later, in the 1950s and 1960s, a series of locks and dams were constructed to extend navigation to points upstream.

The early dams built to harness the waterpower exposed the limestone to freezing and thawing forces, narrowed the channel, and increased the damage from floods. A report in 1868 found that only eleven hundred feet of the limestone remained upstream, and if it were eroded away, the falls would turn into a rapids that would no longer be useful for waterpower. Meanwhile, the St. Anthony Falls Water Power Company approved a plan for the firm of William W. Eastman and John L. Merriam to build a tunnel under Hennepin and Nicollet Islands that would share the waterpower. This plan was met with disaster on October 5, 1869, when the limestone cap was breached.

The leak turned into a torrent of water coming out the tunnel. The water blasted Hennepin Island, causing a 150-foot (46 m) chunk to fall off into the river. Believing that the mills and all the other industries around the falls would be ruined, hundreds of people rushed to view the impending disaster. Groups of volunteers started shoring up the gap by throwing trees and timber into the river, but that was ineffective. They then built a huge raft of timbers from the milling operations on Nicollet Island. This worked briefly, but also proved ineffective. A number of workers worked for months to build a dam that would funnel water away from the tunnel. The next year, an engineer from Lowell, Massachusetts recommended completing a wooden apron, sealing the tunnel, and building low dams above the falls to avoid exposing the limestone to the weather. This work was assisted by the federal government, and was eventually completed in 1884. The federal government spent $615,000 on this effort, while the two cities spent $334,500.

The story of Minneapolis begins at the Falls of St. Anthony, the only true waterfall on the Mississippi River. This waterfall was transformed from a beautiful and sacred site to an engine that powered the city and the region. Today St. Anthony Falls is the center of a thriving Minneapolis Riverfront District, where past and present combine to create a new destination for recreation and commerce.