Local Heroes Exhibit Tells Compelling Stories

Saturday, May 1, 2021 at 2:10PM |

Saturday, May 1, 2021 at 2:10PM |  Doug Verdier |

Doug Verdier | Article by Doug Verdier

A current exhibit at the Hennepin History Museum is not only informative and interesting, but timely as well. Titled Local Heroes, the exhibit focuses on many of the unsung healthcare professionals and caregivers who were trailblazers in Hennepin County between the 1870s and 1970s.

Hennepin History Museum, 2303 3rd Avenue S, Minneapolis, MN 55404Visitors to the museum will recognize numerous parallels between the challenges faced by the individuals featured in the exhibit, such as today’s battle with the COVID-19 pandemic, and other issues familiar today. A combination of historic photographs, artifacts and detailed descriptions tells a rich and compelling story as visitors progress through the main floor gallery.

Hennepin History Museum, 2303 3rd Avenue S, Minneapolis, MN 55404Visitors to the museum will recognize numerous parallels between the challenges faced by the individuals featured in the exhibit, such as today’s battle with the COVID-19 pandemic, and other issues familiar today. A combination of historic photographs, artifacts and detailed descriptions tells a rich and compelling story as visitors progress through the main floor gallery.

Adding to the atmosphere of the chronologically arranged exhibit are a number of portable hospital room dividers that help separate the various displays and help guide visitors through the exhibit.

As noted above, many of the individuals featured in the exhibit are not well known outside of the local healthcare community. This exhibit, which is scheduled to run through September 11, 2021, will help remedy that situation and recognize people today whose contributions to their profession provided the groundwork and direction for those who would follow.

Two "Local Heroes” whose achievements are highlighted in the exhibit are:

Dr. Harry M. Guilford (1872 – 1963)

When the influenza pandemic arrived in Minnesota in October 1918, doctors and health administrators disagreed about the best way to contain the virus. Most supported such countermeasures as encouraging the public to wear masks crafted from layered cheese cloths. However, other topics caused division. Dr. Harry M. Guilford, the health commissioner for Minneapolis, encouraged a more aggressive approach. On October 12, Guilford closed most public spaces, including schools, churches, clubs, and movie theaters. Some doctors considered the decision too drastic. However, as the infection rate continued to climb (by December, there were 15,703 reported infections and 887 deaths in Minneapolis alone), more doctors began to recognize the wisdom of the decision.

Members of the public also disagreed with Guilford’s decision. After a meeting with Minneapolis ministers, Guilford amended closing churches entirely to permitting them to open at 25 percent capacity. His most dramatic clash was with the Minneapolis Board of Education. Led by Henry Deutsch, the board voted to defy the school closure and open on Monday, October 21. Deutsch insisted that the safest place for children to be during an outbreak was in school. Guilford argued that schools remaining open would lead to greater transmission. The disagreement was resolved when Lewis Harthill, Minneapolis police superintendent, arranged a meeting with the school board. The board rescinded their decision and the schools closed again after being open for half a day.

Minneapolis schools and other public places reopened on November 15 but were quickly closed again when a second outbreak surged through the community. On December 30, schools were reopened a third time with precautions implemented by Dr. Guilford, such as setting a quarantine period of ten days after a child was sick with the flu. The goal was to prevent a third outbreak.

By spring of 1919, influenza cases and deaths in Minneapolis started to drop back to average numbers. However, the flu never disappeared, and different strains of influenza still continue to infect people around the world today. Despite medical advances, medical professionals still don’t completely understand what made the 1918 influenza so deadly. Research on the 1918 virus continues as medical professionals seek to understand the epidemics and pandemics of the past to better protect the world in the future.

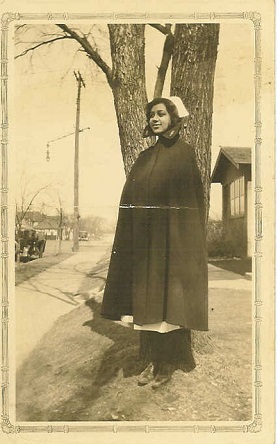

Frances McHie Rains is pictured here in uniform while she was a student at the University of Minnesota School of Nursing. Photo courtesy of Benjamin McHie.Frances McHie Rains (1911 – 2006)

Frances McHie Rains is pictured here in uniform while she was a student at the University of Minnesota School of Nursing. Photo courtesy of Benjamin McHie.Frances McHie Rains (1911 – 2006)

After graduating in 1929 from South High School in Minneapolis, Frances McHie applied for admission to the University of Minnesota School of Nursing, but her application was denied because she was Black. With the help of local African-American activist W. Gertrude Brown, and Democratic legislator Sylvanus A. Stockwell, McHie brought this injustice before the Minnesota State Legislature. When McHie read her rejection letter from the University, the assembly was outraged, and the lawmakers voted that she be admitted to the School of Nursing immediately. Thereupon, McHie became the first Black woman admitted to the University of Minnesota School of Nursing. However, she still faced a deeply rooted culture of racism and systemic discrimination at the University. Nonetheless, McHie graduated from the School of Nursing in 1932 at the top of her class with a double major in education.

McHie continued to trailblaze throughout her long and successful career as a pioneering nurse, educator, and activist. After graduation she became the first Black nursing supervisor at Minneapolis General Hospital (now HCMC). Later, she was the first African-American to work with the Visiting Nurses Association in New Orleans, and she also helped to break the color barrier at Herman Kiefer Hospital in Detroit. McHie went on to became Associate Professor and assistant to the Director of the School of Nursing at Tuskegee Institute and Meharry Medical College in Nashville.

McHie married Dr. Horace Rains in 1951 and settled in Long Beach, California, eventually starting a family. She continued to work in healthcare. In 1953 she became one of the first African-Americans to teach at the University of Southern California General Hospital in Los Angeles. She also devoted a great deal of time to community service. She served as an officer in the Long Beach branch of the NAACP and founded the Long Beach National Council of Negro Women. She died in 2006 at the age of 95.

In 2019, the Frances McHie Nursing Scholarship was established at the University of Minnesota by her nephew, Benjamin McHie, to honor her memory, build on Black history in the medical profession, and support careers in nursing. This scholarship strives to combat racism in the field of healthcare, just as Frances McHie Rains did throughout her life and career.

Moving among the various historic images, artifacts and descriptions of the people, places and events of 100 years in Hennepin County gives one a new appreciation for the dedication and contributions to healthcare by the individuals represented. The challenges these people faced during their lives cannot be overstated. One can’t help but reflect on the parallels of the healthcare environment then and today.

Local Heroes is an important collection of a part of our past that recognizes and honors those who lead the way and inspired today’s medical and healthcare workers. Most of the people represented are not well known. Many of the buildings pictured in the exhibit have been replaced. And medical devices and instruments in use today are quite different from those of yesteryear.

But challenges remain and are being met every day by a new generation dedicated to the health and well-being of everyone. These current “Local Heroes” will continue the work and legacy of those honored in today’s exhibit. And years from now our descendants will honor them.

Thanks to Alyssa Thiede, Hennepin History Museum Curator, and Hannah Dyson, Hennepin History Museum Research Assistant for their contributions to this article.

- - - - - - - - - - -

While the Hennepin History Museum is once again welcoming visitors, masks are required by persons age 6 and older. Also, visiting this museum requires the use of stairs. In addition to the physical exhibit, Local Heroes also is available online at www.hennepinhistory.org.