Father Louis Hennepin: Man, Myth, Legend.

Tuesday, November 30, 2021 at 5:34AM |

Tuesday, November 30, 2021 at 5:34AM |  Michael Rainville Jr |

Michael Rainville Jr | Article by Michael Rainville, Jr.

What is the story behind Father Louis Hennepin? It’s a name so common around here that we don’t think twice of it. There’s Father Hennepin Bluff Park, Hennepin Island, Hennepin Avenue, Father Louis Hennepin Bridge, and Hennepin County. He was the first non-Native American to set eyes on Owahmenah, “falling water” in Dakota, Kababikah, “severed rock” in Ojibwe, or St. Anthony Falls, but that’s just the middle of the story. Well here’s the beginning and the end.

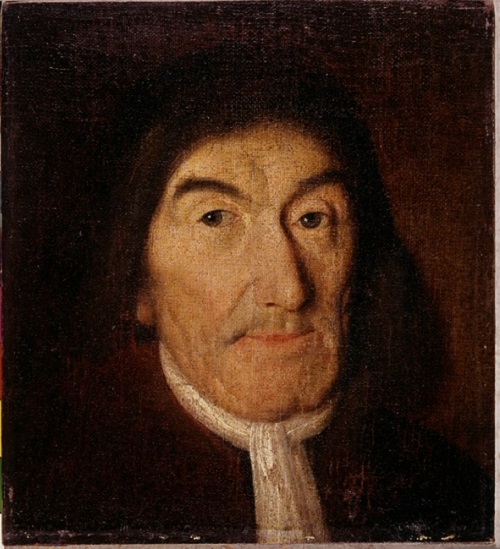

A portrait of Hennepin from 1694.

A portrait of Hennepin from 1694.

Father Louis Hennepin was born in 1626 as Antoine Hennepin in Ath, Spanish Netherlands, what is now Belgium. Growing up he traveled around Europe as much as he could, and by the time he turned twenty, he joined the Récollets, also known as the Franciscan Order. During his time studying at a convent in Bethune, France he quickly became interested in stories of missionaries traversing the wilderness of undiscovered lands. In 1673, he was sent to Maastricht, Netherlands and became a military chaplain. A year later he was sent to the Battle of Seneffe, a part of the Franco-Dutch War, where he ran into Daniel Greysolon Dulhut, the namesake for Duluth. After the battle, he was ordered to make his way to La Rochelle, France where he would soon set sail for the New World.

For his first three years in Quebec, he would follow hunters and trappers to their camps and visit Native American settlements only bringing a portable altar, a blanket, and a mat made of rushes to sleep on. He took notes during all his journeys and would report back to French officials on his discoveries. During this time, he stumbled upon his first claim to fame, Niagara Falls, and he became the first non-Native American to document the falls. In 1678, a French explorer by the name of Robert Cavelier de La Salle made his way to Quebec with permission from King Louis XIV of France to explore the Mississippi River and the land that drains into it. Boarding a boat near Niagara Falls, the exploration party became the first non-Native Americans to navigate Lakes Erie, Huron and Michigan.

Once landing in Green Bay, the party traveled by canoe and foot, and by the time they reached Fort Crèvecoeur, near present-day Peoria, Illinois, the food supply was low and they were lacking the necessary materials for navigation, so many members of the party, including La Salle, deserted and decided to head back to Niagara in order to rethink their plan. Only three men remained; Father Hennepin, Michel Accault, and Antoine Auguel Du Guay. Following the Illinois River, they made their way to the Mississippi. Once the ice left the river, they made their way upstream, and in mid-April of 1680, they were greeted at Lake Pepin by thirty-three canoes paddled by 120 Dakota. The three men were then taken upstream to Kaposia where the elders decided what to do with them. They were then taken by foot to a village along the south shore of Mille Lacs where they stayed for two months.

Famous 1905 painting by Douglas Volk.

Famous 1905 painting by Douglas Volk.

A hunting party from the village then took the men down the Rum River to the Mississippi and the Dakota agreed to let them paddle down to the Wisconsin River where they could pick up supplies. The three men paddled their way down and on July 6th, 1680, they approached a roaring waterfall Hennepin eventually named after his patron saint, St. Anthony of Padua. The men soon made their way to Prairie du Chien, where the Wisconsin and Mississippi Rivers meet, and started the journey back upstream. With a canoe fully loaded with supplies, the three men struggled to paddle against the ripping current and were met by Daniel Greysolon Dulhut once again. Dulhut and Hennepin recognized each other from their previous meeting during the Battle of Seneffe. Dulhut’s party helped the three men back to Mille Lacs and over a month later, Dulhut negotiated with the Dakota chief to allow them to return home to Quebec. The men once again packed up their canoes and started paddling home, and on their way, Father Louis Hennepin set his eyes on what he called “the Niagara of the West” for the last time.

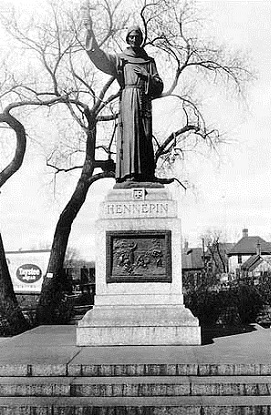

Statue of Hennepin located in front of the Basilica of Saint Mary.Once returning to Europe, he seemed to have made a few enemies, including King Louis XIV who said he would be arrested if he ever set foot in New France again. His eccentric personality and passion to become an explorer might have bolstered his ego a bit too much. He wrote three books about his travels and went into great detail in all of them. In his first book, he even slandered La Salle by saying, “Sieur de La Salle wanted all the glory and secret knowledge of this discovery for himself alone. This is why he sacrificed several persons to prevent them from publishing what they had seen and from foiling his secret plans.”

Statue of Hennepin located in front of the Basilica of Saint Mary.Once returning to Europe, he seemed to have made a few enemies, including King Louis XIV who said he would be arrested if he ever set foot in New France again. His eccentric personality and passion to become an explorer might have bolstered his ego a bit too much. He wrote three books about his travels and went into great detail in all of them. In his first book, he even slandered La Salle by saying, “Sieur de La Salle wanted all the glory and secret knowledge of this discovery for himself alone. This is why he sacrificed several persons to prevent them from publishing what they had seen and from foiling his secret plans.”

Paranoia and his need for being recognized for his discoveries took over Hennepin during his later years and passed away in Rome around the year 1705. Not much is known about his life other than what he wrote about in his books and what other explorers wrote about if they ever traveled with Hennepin. Some sources say he was born in 1626 and some say 1640. Some sources say he greatly exaggerated his discoveries in his books, and some say he returned to Quebec to a hero’s welcome. However, there’s one thing that’s for certain; Father Louis Hennepin will always be a legend in the Mill City.

- - - - -

Click here for an interactive map of Michael's past articles.